On Saturday, August 15th, the Indian government prohibited text messages, specifically mass texts, for the next 15 days. The goal behind the Indian texting ban is to reduce panic after mass texts warning of ethnic violence sent tens of thousands of Indians fleeing from areas believed to be unsafe.

Limitations were originally set to 5 mass texts per user per day, but some mobile carriers interpreted that as 5 texts (even to a single recipient) per day. Since the original ban on August 15th, this 5 has been raised to 20 group texts per user per day, again with some carriers interpreting that as 20 texts total.

Of course, the ban limits texts that have nothing to do with rumors of violence, so texters in India are resorting to creative ways to let their friends know they’re running fifteen minutes late, often by installing an IMing app (or making use of one already gathering electronic dust on their smartphone).

Of course, the ban limits texts that have nothing to do with rumors of violence, so texters in India are resorting to creative ways to let their friends know they’re running fifteen minutes late, often by installing an IMing app (or making use of one already gathering electronic dust on their smartphone).

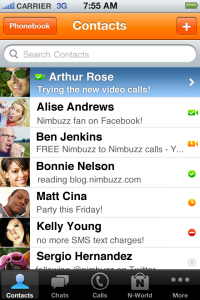

Mobile instant messenger Nimbuzz, a chatting and VOIP app with 17 million users in India, has reported an increase in downloads of more than 20% over usual since the Indian texting ban. While this is in effect, and while users may feel unsure about SMS message content, we can expect more downloads and more active users of this and other chat apps.

Mass text messaging is also a prevalent form of advertising in India, but I can’t quite make myself feel badly for would-be advertisers affected by the ban. (When I lived in Beijing, another area where SMS adverts are quite popular, my phone buzzed constantly with mass advertising texts.) I’m sure it won’t be too long before quick-witted advertisers find a way to get around the mass-text ban, and reach their targets.

I don’t want to speculate on the reasons behind the dangerous rumors, but I’m curious if those who started the panic-inducing messages by text will switch to similar behavior on chat apps and social networks, or if the anonymity of pre-paid SIM cards provides an essential cover for starting dangerous rumors.