As the old saying goes, ‘with great power comes great responsibility.’ No sooner had Zoom become the go-to video app, people started taking shots at it. Questions were asked about its capacity, its capability, and its security. It didn’t take long for several major news outlets to begin suggesting that it was unsafe or compromised and that people should consider using another video-sharing app like Houseparty instead. That, too, backfired. Houseparty was suddenly accused of being so lax with security that people’s bank details, social media passwords, and other private information were being hacked through the app, and so people deleted it and went back to Zoom. Houseparty has consistently denied the claims and is now offering a financial reward for anyone who has information about what it believes to have been a targeted smear campaign in the media.

These are clearly tense and troubled times in the battle for video-calling supremacy, and frankly, for those of us who don’t work for any of the companies involved, it’s a little tiresome. All we want is a piece of software that allows us to communicate with the people we love easily and safely. While it’s true to say that no operation carried out across the internet can ever be one hundred percent secure, Zoom would like us to believe that they’re as safe as it’s reasonably possible to be. Some people disagree with that. Some people – especially the people who write for tabloid newspapers – keep running stories about something called ‘Zoombombing. What is zoombombing, though, and is it something that you ought to be afraid of?

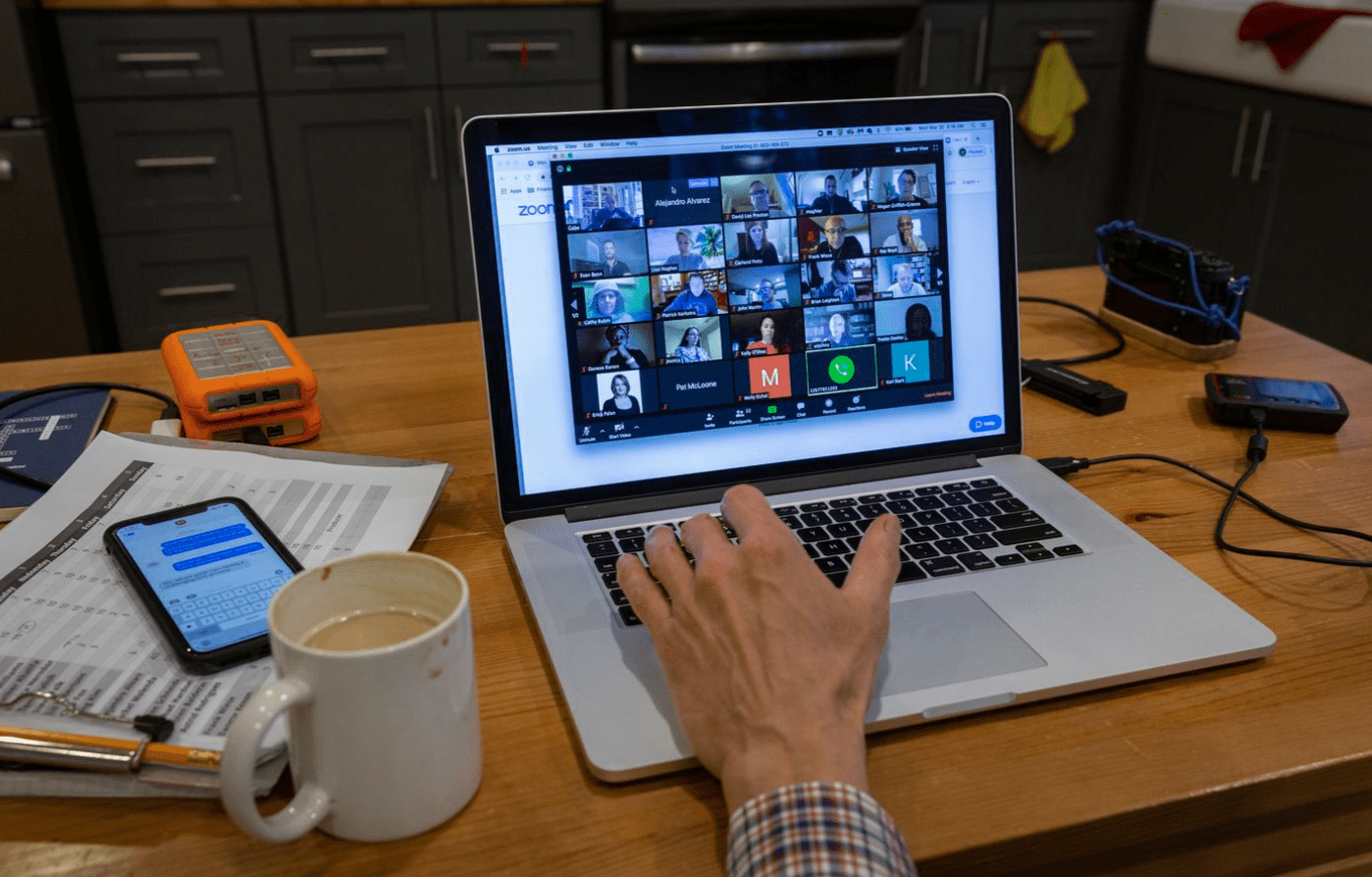

Put simply, Zoombombing is the practice of crashing someone else’s Zoom meeting uninvited and then disrupting the meeting once inside. That disruption usually comes in the form of sharing graphic, distressing, or otherwise unwanted content with the people already in the conference. Taking advantage of the fact that anyone in a Zoom meeting can share their screen with other participants, they can effectively ‘force’ other people to see whatever they want them to see, with the only recourse for the offended parties to shut the meeting down and try again. It’s like photobombing, only more malicious. Once a session has been ‘zoombombed,’ it’s difficult to rescue it. The offending participant can be kicked out of the meeting, but they’ll often come back via a series of aliases and sock puppet accounts.

More often than not, the zoombombers will have access to the meeting ID because the host of the meeting has published it in a public place online. On other occasions, though, the zoombomber will simply enter random strings of numbers until they hit upon an active meeting. For them, it’s the same as playing the most popular slot game Wolf Gold. On the majority of occasions, nothing happens when you spin the reels of an online slots game. When you win nothing, you just spin the reels again and see if you’re any luckier the next time around. Eventually, through patience and application, you’ll strike lucky and win something. In online slots terms, that’s either a jackpot or a cash win. In terms of zoombombing, that’s access to an ongoing meeting. Online slots players don’t tend to want to cause other people harm, though. Zoombombers do.

Zoom was vulnerable to this type of attack because it had never been given any reason to expect use or abuse on this kind of scale before. Zoombombing didn’t exist because there weren’t enough meetings happening on the platform to try to infiltrate, and nor was there any reason to want to. The sudden explosion in popularity has, by the company’s own admission, caught them on the back foot. They’ve made a few changes to their standard security settings and options since the problem was first reported, though, and so long as users follow common sense and double-check their settings before hosting a meeting, there’s nothing to be worried about.

The most important thing for any Zoom host to do before creating a meeting is to ensure that it’s protected with a password. With a password in place, nobody can get in without an invitation. That’s fine for small gatherings of up to ten people, but there are still potential vulnerabilities when a password is circulated more widely – for a live stream music performance, for example. In those instances, users can either change the settings of the app so that only the host can share their screen or only allow screen sharing to be performed by specified approved participants. A host can also selectively mute some or all of the other participants if they wish to, thus preventing the risk of a noise interruption.

With all of the above in mind, it’s clear to see that zoombombing doesn’t have to be a problem if you don’t allow it to become one. Don’t host a meeting without a password, don’t circulate a password widely, and ensure that you remain in control of who can and can’t share screens or audio inside a meeting, and you’ll be fine. These are all common-sense steps, and if all users follow them, zoombombers can’t get into a meeting no matter how hard they try. These are trying times for all of us, and we’re relying on video communications tools to stay in touch now more than ever before. It’s a shame that we can’t trust everybody to use these tools responsibly, but if we all take ownership of the security tools that come with the app, there’s nothing to fear.